It’s said a reporter’s story is only as good as her notes.

Taking good notes seems like an easy task. You go to interviews, ask important questions, take good notes, and write a good story. It’s a piece of cake, right?

The problem is that taking good notes while you’re listening, observing, thinking about your next inquiry or a necessary follow-up question, and attempting to comprehend what the source is saying is not that easy to do.

The problem is that taking good notes while you’re listening, observing, thinking about your next inquiry or a necessary follow-up question, and attempting to comprehend what the source is saying is not that easy to do.

To make matters worse, you may be doing all of this while you’re standing in shoes that hurt on the side of a busy interstate, questioning a firefighter who is anxious to return to fighting the grass fire you’re interviewing him about. Did I mention you haven’t eaten lunch and you’re starving?

Trust me, I speak from experience, interview conditions are not always ideal. I interviewed Oklahoma’s 25th governor while walking him to the bathroom.

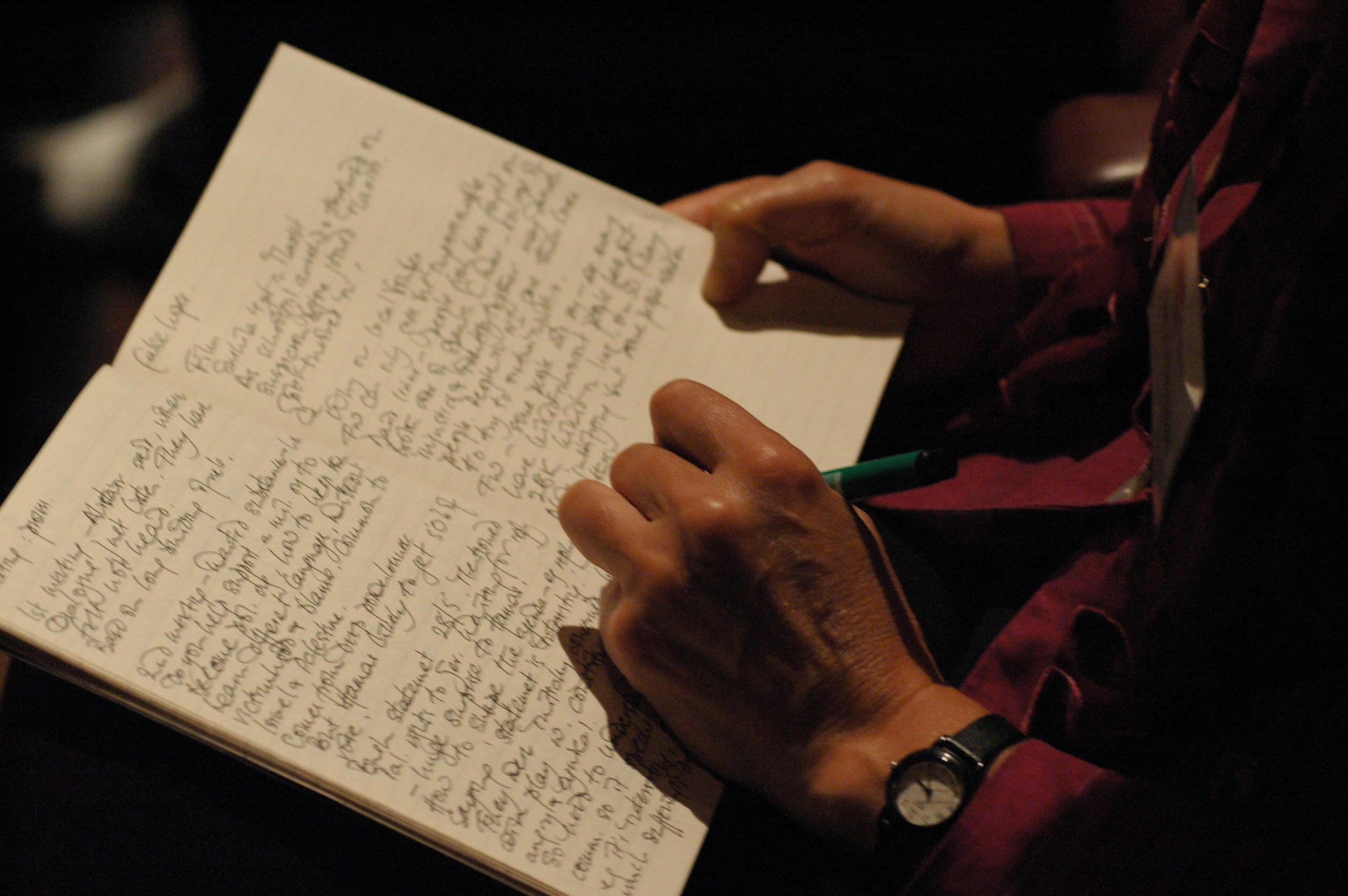

You’ll return to the newsroom with a notebook full of scribbles if you’re not careful.

Good interviewing takes practice, and good note taking is a skill you must hone right from the start. To turn your journalistic scribbles into professional notes, consider:

Start with questions

Start each interview with a numbered list of questions that you must be sure to ask. Write the question number next to the appropriate response. This helps you keep the source’s words in context. Just remember not to be married to the list. Always ask follow-up questions as the interview develops.

Identify sources

Always get the source’s correctly spelled name, official title and a variety of contact numbers. Don’t trust business cards unless the source refers to directly to the card. I’ve been in the same position for 10 years. I’ve had three or four different titles on my business cards. My title actually changed only once. If the source refers you to his or her business card, verify that it’s correct, then staple it in your notebook.

Leave space

Don’t crowd your notebook. Leave plenty of space to add to thoughts or elaborate on points.

Drop digital

I hate digital recorders because they encourage lazy note taking. Never allow a digital recorder of any kind to keep you from taking good notes. As soon as you do, it will fail you. I learned this the hard way when I had to reinterview an attorney about his client’s controversial case because my audio recorder went dead during the interview. He was unhappy about being interviewed a second time and his canned quotes weren’t nearly as telling as his original responses.

Write everything

Reporters always have more information than what ends up in a story. Write down everything. It’s acceptable to have way more information then you’ll ever use in a story. It’s unacceptable to need information that you’re pretty sure a source provided but you didn’t document.

Carry supplies

Journalists always should have at least two pens and paper with them. Always. Murphy’s Law tells you the first pen will run out of ink right in the middle of the interview or your notebook will run out of paper at the most important point in the meeting. It’s a blow to your journalistic professionalism to have to beg supplies from a source.

Keep time

Jot down the time every five minutes or so. This helps you remember the rhythm of the interview. It’s especially helpful for keeping yourself respectful of your source’s time and for pacing feature stories.

Draw charts

I find charts especially helpful in interviews with multiple sources. For example, any time I was covering a city government or school board meeting for the first time, I would draw the board members’ seating chart, label it with numbers and then write the correct name spelling of each board member. During the meeting, this allows you to use the speaker’s number when quoting him instead of repeatedly writing his name. It’s much faster to write and circle the number three than it is to write “Schiermeyer said” repeatedly.

Observe the space

You can learn a lot about people by observing the things with which they surround themselves. It’s helpful to jot down a few details about someone’s home, office or even his personal appearance to help add detail to the story.

In second semester as a college professor my feature writing students were writing profiles about professors. A student chose to profile a philosophy professor who also is the minister of a local church. We were discussing her story in class and what she learned when visiting his office. She talked about stacks of books and piles of papers—typical stuff for a college professor’s office. She also described artwork obviously created by his children that was displayed. Then she admitted there was an item in his office that made her really curious but about which she was afraid to inquire. The professor had a painting of a full-frontal nude woman in his office. Given the location and his position of authority in the church, the painting surprised the student. I suspect it also embarrassed her because she was too afraid to ask him about it. I made her go back to interview the professor just about the painting. You know what’s worse than asking a professor about the nude painting in his office during a series of other questions? Asking a professor about the nude painting in his office as the main subject of the interview. The student discovered that the professor’s wife, an artist, had given him the painting. She also learned an important lesson about observation and follow-up questions. Always ask.

Use your senses

One of my favorite leads I’ve ever read was written by my reporting partner when she was assigned to cover the fair for the state newspaper where we worked. It read:

Six, eight, four, seven.

Moo, moo.

Multiplied by…

Moo.

Time to feed the cattle.

As Michelle Seidl punches out math problems on a calculator, she says she doesn’t have a hard time focusing on her homework in the midst of bulls and heifers waiting for their daily feeding time.

In Livestock Barn No. 3 at the State Fair of Oklahoma, it looks almost like a classroom study session around 5 or 6 p.m. each day – except the smell of cows and wood chips doesn’t usually pervade classroom study halls.

Teen-agers and younger children sit near the stalls where their livestock is tied and work out math problems, write essays and plan next week’s science experiment.

“When you’re not busy with the cattle, you’re doing your homework,” the Garber High School freshman said.

Michelle Seidl, 14, her brother Eddie, 12, and their older sister, Amanda, have been showing livestock in the state fair for 12 years. This year, they brought two bulls and seven heifers.

She was there with the sources. She saw it. She heard it. She smelled it. It’s obvious to the reader in the way she used her senses in her reporting.

Avoid temptation

There legally is no such thing as off-the-record information. When a reporter agrees to take information off-the-record, the question becomes one of ethics. An ethical reporter does not use information she takes off the record. Reporters also know that some of the best information and quotes are given when a source isn’t worried about being documented. I never tempt myself with off-the-record information. I just don’t write it down. If you don’t document it, you won’t be tempted to use it.

Save often

It’s always better to do interviews in person so you can observe sensory details and develop a professional relationship with the source. However, phone interviews are a necessary part of the busy news cycle. If you are interviewing someone via telephone, you may be tempted to type notes on your computer. If I’m being honest, this is my favorite note-taking method. I can type so much faster than I can write. Plus, the information already is in a text document and ready to be formed into a story.

Two note-taking tips are necessary specifically for typed interviews. First, save often. Power flickers and computer fails can cost a lot in time and efforts. Second, be sure to keep a saved copy of just your notes before you morph them into a story. You may need to retrieve things you deleted during the process.

Transcribe quickly

Transcribe or clean up your notes as soon as possible after the interview, while everything still is fresh in your mind. If you didn’t document a quote exactly or you aren’t certain what something says, you can’t use it.

Destroy them

Know your publication’s policy on whether to keep notes and how long to do so. I was taught to destroy notes as soon as a story runs, that way they can’t be used against you in court. Other reporters I know were taught to keep notes to protect you from the same types of legal issues. Ask your editor.

Don’t be cute

Never write jokes or humorous anecdotes in your notes. An editor once told me about a time when he got bored in a city council meeting and killed time writing funny comments to himself about the mayor and council members. He then forgot his notebook in the council chambers. The city clerk called him the next morning to come pick it up. He, of course, assumed at least she had read it. What a terribly unprofessional learning experience!

Write soon

It’s also helpful to write the story as soon as you can after an interview. Even the best notes can be a bit confusing after sitting for a while.

Identify direct quotes

I have a simple way of telling when I wrote a source’s quote word-for-word and when I need to paraphrase. If I was able to get a precise quote, I put quotation marks at the beginning and end of the sentence(s). If not, I don’t close the quotes at the end of the sentence(s). This signals to me that I need to paraphrase the information.

Journalistic interviews typically don’t happen under perfect conditions, and it’s easy for your carefully elicited information to become scribbles in your notebook. Good note taking is a skill you must hone right from the beginning of your career because solid interviewing practices are the foundation for great stories.